Tabula rasa

Concert recording of the premiere of Tabula rasa. Courtesy of Estonian Public Broadcasting.

Tabula rasa (1977). Concerto for two violins, string orchestra and prepared piano

The central work in Pärt’s instrumental music, the double concerto Tabula rasa has become one of the cult pieces in the music world and has prompted many composers and musicians, as well as concert audiences, to listen to and understand music in a completely new way. This composition also became a turning point in Arvo Pärt’s career, introducing the expressive possibilities of the tintinnabuli style for the first time in a large-scale musical composition.

Violinist Gidon Kremer has described Tabula rasa as a declaration of silence, a manifesto of concentrating on important things. He has also admitted that this piece changed his life. Manfred Eicher, the head of the record label ECM, has recalled the first time he heard Tabula rasa: driving in a car, without knowing the name of the composer or the title of the piece. This experience became a trigger for creating the ECM New Series in 1984. Tabula rasa was the first record in the series and also brought wider recognition to Arvo Pärt.

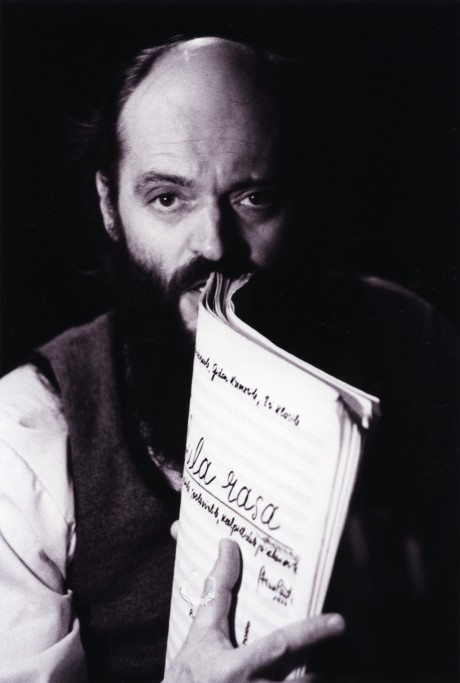

A double concerto for two violins, string orchestra and prepared piano was composed at the request of the violinist Gidon Kremer in 1977. The piece was premiered on 30 September 1977 at Tallinn Polytechnic Institute by the chamber orchestra of the “Estonia” State Academic Theatre, conducted by Eri Klas, a talented young conductor and a good friend of Arvo Pärt. The violin soloists were also young musicians, soon to be world famous Gidon Kremer and Tatiana Grindenko, while Pärt’s close friend, the composer Alfred Schnittke played the prepared piano. Tabula rasa is dedicated to Eri Klas, Gidon Kremer and Tatiana Grindenko.

Gidon Kremer and Tatiana Grindenko rehearsing Tabula rasa before the premiere, September 1977. Photo: Arvo Pärt Centre.

However, the road to the premiere was not a smooth one. The apparently simple music proved incomprehensible to the performers. It is not an overstatement to say that the musicians, who were used to virtuosity and artistry, were suddenly face to face with the basic elements of music in Pärt’s score: triads and scales. This required a completely different approach, both interpretatively and psychologically. Gidon Kremer admitted that he was surprised by the reduced musical language of the piece and it took him a long time before finally realising the subtlety and intelligence hidden in these sounds. Nora Pärt, the composer’s wife has recalled that even after additional rehearsals the musicians felt powerless before the composition. However, when they started playing at the concert, all the pieces miraculously fell into place. Nora Pärt:

Never again have I experienced the silence that took over the assembly hall after the premiere.

[Arvo Pärt 70. A radio series of 14 parts by Immo Mihkelson, Klassikaraadio, 2005, part 7.]

The two movements of Tabula rasa are in contrast with each other both in terms of mood and speed. While Ludus (Latin for “game”) consists of eight variations and a forceful cadenza, in Silentium (Latin for “silence”), the slow second movement, Pärt again uses the prolation canon known in his earlier works: different voices move at different rhythmic speeds. Pärt has reserved the fastest rhythmic speed for the bass voice and the slowest for the first solo violin. It is the second movement that requires utmost concentration from the musician. The main focus of the piece consists in the need to listen to the silence and find its colours, delve into every single note and approach the music in a completely selfless, humble way. Conductor Andreas Peer Kähler has compared Silentium with a lie detector which, as if making the musician stand completely naked on the stage, leaves no chance to hide behind anything.

The phrase tabula rasa comes from ancient philosophy and is directly translated as “blank slate” or “erased slate”. Although the term has acquired somewhat different meanings and interpretations over the centuries in Western culture, it is mostly associated with the Aristotelian notion of a human soul that is born into this world as pure and empty of all experiences or ideas, at the same time having a special potential in the anticipation of these ideas and experiences.

Arvo Pärt:

Before one says something, perhaps it is better to say nothing. My music has emerged only after I have been silent for quite some time, literally silent. For me, “silent” means “nothing” from which God created the world. Ideally, a silent pause is something sacred… If someone approaches silence with love, then this might give birth to music. A composer must often wait a long time for his music. This kind of sublime anticipation is exactly the kind of pause that I value so much.

[Jeffers Engelhardt, Perspectives on Arvo Pärt after 1980, The Cambridge Companion to Arvo Pärt. Ed. by Andrew Shenton. Cambridge 2012, p 35.]