Biography

A family of composers

It’s a few years after World War II, composer Hendrik Andriessen is working on his opera Philomela. His son Louis is nine years old. When Hendrik has some friends visiting, Louis enters the room: “I’m also writing an opera”, he says. One of the guests asks with interest which text he has chosen. Many years later he reflects on this moment:

“I hadn’t thought of that. That you would need a text for an opera. But I liked the idea of working on your own in a quiet room. “

[Louis Andriessen and Mirjam Zegers, Jongensjaren, 2009]

Seven years later (1956) Louis Andriessen writes his Sonata for flute and piano [Sonate voor fluit en piano, published in 1962], the earliest of his official works.

Andriessen'a early compositions demonstrated exploration of the dodecaphonic style the second Viennese school and influences of Darmstadt serialism and other avant-garde ideas (e.g. Séries for two pianos, Nocturnen for two sopranos and orchestra, Anachronie I). However, these fascinaions were short lived and soon replaced by new creative ideas. As Andriessen recollected:

It wasn’t so much Schönberg and Webern that I liked, but what came after: Boulez and Stockhausen, sounds that we had never heard before. But as I developed, the old anti-German, anti-romantic attitude came increasingly to the forefront and that’s why this influence never got so strong.

[Frans van Rossum and Sytze Smit, Louis Andriessen: After Chopin and Mendelssohn we Landed in a Mudbath, Key Notes: Musical Life in the Netherlands 28 (March 1994), p. 11.]

Jazz influences and popular culture

Jurriaan Andriessen, an older brother of Louis, came back from the US in 1951 with a number of jazz records to which Louis listened. Two years later, Andriessen discovered the boogie-woogie; the rhythmic ostinato bass figures would eventually form part of the building blocks for his compositions.

He is introduced to bebop by listening to Dutch radio broadcasts by dj and jazz lover Pete Felleman, who also played a lot of big band music. In the seventies Andriessen formed the orchestras De Volharding and Hoketus. Both ensembles continued to exist after he left. In 1973, he conceives On Jimmy Yancey, for nine horn players, piano and double bass, inspired by his admiration for this boogie-woogie pianist. See also this video interview where Andriessen talks about the boogie-woogie influences for this piece. In 1990, he composes Facing Death for amplified string quartet.

“In 1989 when I was teaching in Buffalo, Miles Davis’ Autobiography was published. While reading it, I suddenly knew what the subject should be of my piece for the Kronos Quartet – early be-bop licks and especially the work of Charlie Parker. I wanted to do the impossible – be-bop is not at all idiomatic for string instruments. But be-bop had been an important influence on my musical development when I was young, and I decided to do something with this music from my youth.”

[Louis Andriessen, Composer’s note on www.boosey.com]

Between 1976 and 1980 Andriessen composes music for several theatre productions for Toneelgroep Baal, including an alternative Mattheus Passion. He also composes for dance productions, e.g. for Dubbelspoor (1980) by choreographer Beppie Blankert.

In the nineties, he writes music for the film M is for Man, Music, Mozart by Peter Greenaway. With him, he also works on the opera Rosa (1994). Another filmmaker with whom he works is Hal Hartley including the films The New Math (s) (2000) and the film opera La Commedia (2007).

Breaktrough

November 28, 1976, Concertgebouw, Amsterdam: De Staat for 4 female voices and large ensemble premiers. The work is instantly considered as the start of Andriessen’s international breakthrough. The text for this work is derived from Politeia by Plato.

Plato wants very strict rules in the ideal state he describes. This is typical for totalitarian thinkers in power. The advantage of this way of thinking is that everything is very simple, undialectical. Plato was for me a perfect example to explain to what I call the ‘vulgar Marxists’ of those days that the problems were far more complicated than they thought. Because even they could understand that Plato was wrong. On the other side: Plato says in the final chorus that you can’t change the laws of music because then the laws of state change. As a composer I regret that he is wrong. Imagine that music would have that power. That would be ideal for composers. The anger of this work comes from my disappointment about the fact that Plato was wrong. I have sympathy for a situation in which music becomes very important again, as with Plato, when people knew how important art is.

[Louis Andriessen, Gestolen tijd, 2002]

'Actie Notenkraker'

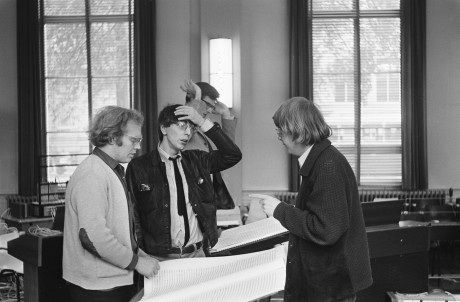

In 1966 Louis Andriessen, Reinbert de Leeuw, Misha Mengelberg, Peter Schat and Jan van Vlijmen (all former students of Kees van Baaren) and many others try to get the Italian composer Bruno Maderna appointed as the conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra next to Bernard Haitink, because he is so well versed in the 20th century repertoire.

November 17, 1969, Concertgebouw, Amsterdam: about forty young composers, including Louis Andriessen, musicians and supporters attend a concert of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Bernard Haitink. They’re dissatisfied with the way their suggestion for the appointment of Maderna and for adding more modern works to the program were (not) heard by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. When Haitink indicates the prelude, clicking, rustling and whistling sounds made with from frog clickers, rattles, horns and whistles from toyshops come from all sides. Pamphlets are handed out during this so-called ‘Actie Notenkraker’, and Bernard Haitink is called by megaphone to discuss "the program policy and the undemocratic structure of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra".

In 1970 Andriessen decides to never compose for a symphony orchestra again. In the following years, he forms several ensembles such as Orkest de Volharding and Hoketus, in which he often plays instruments himself. Many years later, in 2013, he decides to take an orchestra assignment work again. He composes Mysteriën for the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, that celebrates its 125th anniversary that year. He is willing to do this as the size of the orchestra could be reduced and he’s given the freedom to choose instruments that he normally needs for his pieces, like saxophones and bass guitars. In 2018 a new (commissioned) work will premiere at the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

Social awareness

June 29, 1969, Carré Theatre, Amsterdam: the opera Reconstructie premieres. For several years Andriessen incorporated his social engagement into his music and he’s been writing for several newspapers and literary magazine De Gids.

The ‘Actie Notenkraker’ certainly gave an impulse to contemporary classical music. A few years after the action Andriessen composes the opera Reconstructie with four other Dutch composers, on a libretto by Hugo Claus and Harry Mulisch. It is a tribute to Che Guevara, based on the story of Mozart's opera Don Giovanni. Reconstructie causes, even before finalisation, for hundreds of angry letters and even led to questions in Parliament. Culture Minister Klompé vigorously defends the opera. They argue that it is not the task of the government to interfere with the content of a work of art, even if the artwork is based on a subsidized institution.

In Reconstructie tape and live electronics are used, such as sound distortion. For this purpose, the STEIM foundation is formed (Studio for Electro-Instrumental Music) in the same year.

'Andriessen, the thinker'

June 1, 1989, Het Muziektheater, Amsterdam: De Materie premiers. The work consists of four distinct and independent parts, which also form a unit. For these four parts Andriessen chooses deciding moments from Dutch history: the Act of Abjuration, in which the Dutch States General declared their independence from the king of Spain in 1581; the seventh vision of the 13th century poet and mystic Hadewijch; the abstract paintings by Piet Mondriaan; and the late 19th century texts on love, death and science by among others the ‘Tachtigers’ poet Willem Kloos. The work is full of references to old musical forms and techniques.

“De Materie is primarily the work of Andriessen the thinker: it’s a strand piece, ruled by bar and number, a structure in which numerous extra-musical ideas from science, architecture, religion, history, philosophy, art and literature are united in a contrapuntal network with musical form models. The work seems to be an ode to the flight of the human spirit, and recalls visions of a universal beauty and a higher order in which everything is connected”.

[Frits van der Waa, Louis Andriessen in Het HonderdComponistenBoek, ed. Pay-Uun Hiu, Jolande van der Klis, 1997]

Andriessen's legacy

Louis Andriessen (born 1939, Utrecht), descendant of an illustrious family of musicians, is considered to be the most influential Dutch composer of his generation. That is due to the quality of his music, but also his qualities as a teacher. His oeuvre cannot be summarised in one core sketch, but an important common thread is the constant confrontation with tradition, that developed into a dialogue during the course of his career. His compositions cover nearly all musical genres, and can be characterized by their tendencies to theatre, literature, dance and film. Additionally, Andriessen has been involved with the renewal of the musical practice, and thus played an important role in the development of the Dutch ensemble culture. Andriessen studied composition with Kees van Baaren at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague and from 1962 to 1964 with Luciano Berio in Milan and Berlin.

He raised many foreign students as teacher of composition at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague and was often a guest in e.g. London, New York and Australia. The appreciation for his work seems even larger abroad than in his home country: in 2014 his 75th birthday was celebrated in the U.S. with festivals in Winchester and Washington.

Currently, Andriessen is working on an assignment for the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, which will premier in 2018–2019.