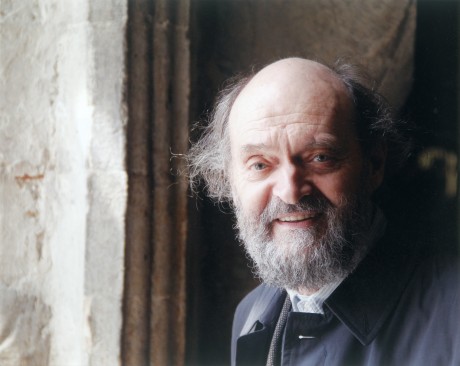

Biography

A boy with a bicycle

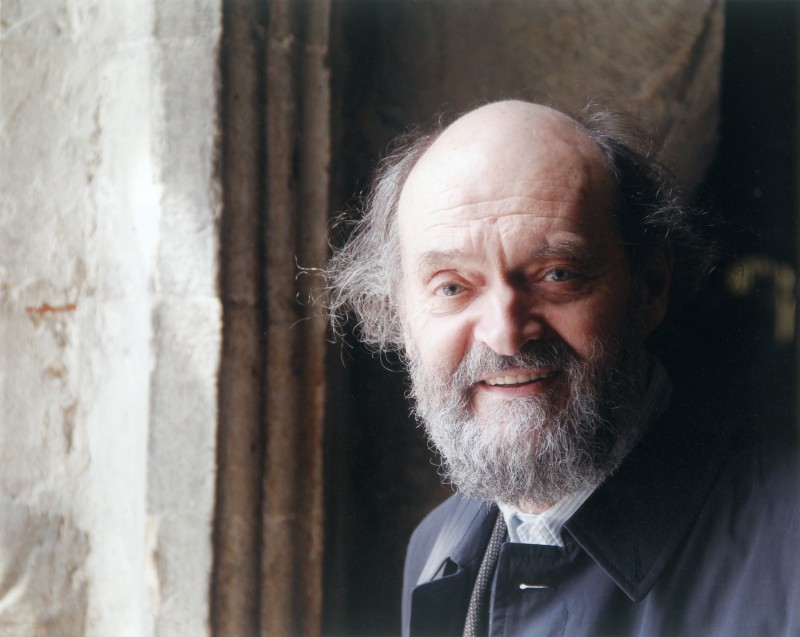

After the Second World War, in a small town called Rakvere, in Estonia, there was a schoolboy who liked to ride his bicycle for hours in the town’s central square. The boy was Arvo Pärt, pretending he was just cycling. But in fact, it was music that made him come to the marketplace of his hometown – music that could be heard from the loudspeakers hanging on the posts. Back then, it was not so easy to get access to the radio, but once you’ve had it, it was a chance to listen to classical music and concert broadcasts.

Arvo Pärt:

Sometimes when the wind carried these sounds into our backyard, it felt like finding the meaning of life …

[Arvo Pärt 70. A radio series by Immo Mickelson, Klassikaraadio, 2005 part 1]

From these years on the need for music and the love for it could not be substituted by anything else. A young man had found his calling.

Arvo Pärt:

My thirst for music was so intense that there was nothing on the horizon that could quench this.

[Ibidem]

Warsaw Autumn as catalyst

It was in September, 1963 when Arvo Pärt visited Warsaw Autumn, Polish festival of contemporary music, which for Pärt as for many other Eastern European composers at that time was one of the few platforms to get in contact with avant-garde music and to meet colleaguse from the West.

Pärt had gained his modernist reputation in Soviet Estonia already with his first compositions, written as a student. Impressions and experiences from Warsaw definitely encouraged Pärt to further and even bolder experiments and exploring new paths.

Only few months after his visit to Warsaw Pärt composed his Perpetuum mobile for orchestra, the first sonoristic composition in Estonian music. Soon after that came a miniature choir piece Solfeggio (1963) – timbre-focused vocal exercise in C Major, text based on the note names do, re, mi, etc; an experimental piano piece Diagramme (1964) – a dodecaphonic work with aleatoric elements, written down in graphic notation; and also Collage über B-A-C-H (1964) – the first collage in Estonian music.

In early 1960s Pärt also took part in the experimental art events called happenings which were initiated by avant-garde writers, artists and musicians. During one of these happenings in January, 1961, in Tallinn Writers’ House it just happened that the violin that according to the stage script had to “go to the surgery“, accidentally caught fire … The scandal with the Soviet officials was unavoidable and Pärt was one of them who had to write an explanatory

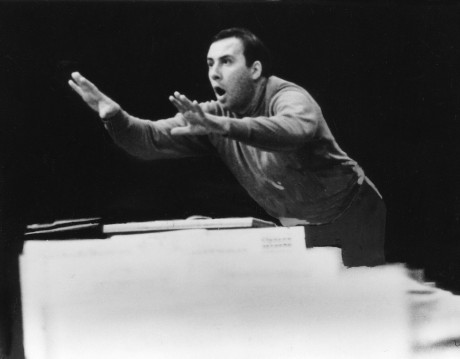

Finding his Credo

November, 1968. The most important concert venue in Tallinn – Estonia Concert Hall – is crowded with people. The Estonian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Choir are at the stage, conducted by Neeme Järvi. And in that deeply anti-religious Soviet cultural room the unexpected latin words “Credo in Jesum Christum“ (“I believe in Jesus Christ“) were heard from the stage, as well as a musical parable on the notes of Prelude in C Major (WTC I) by J. S. Bach. It was the premiere of Arvo Pärt’s Credo. The audience was like thunderstruck and demanded the piece to be repeated immediately.

After that evening Credo was quietly but consistently eliminated from the concert repertoire as well as from the official reports. This significant episode became a landmark in Pärt’s creative life as it fixed his status as a persona non grata. New commissions were out of the question and also his earlier works disappeared from concert and radio programs. “This was my musical death sentence,“ has Pärt later commented. Indeed, Credo led the composer into long creative crisis that went on for eight years and could end only in 1976 when Pärt’s new compositional style – tintinnabuli – was born.

Eight years of searching

The year of 1968 was a turning point. After Credo Pärt decisively gave up all his earlier compositional techniques and styles, sensing the deeper need for his own musical language. Arvo Pärt:

I was left completely naked. It was like turning the new page in my life, or in music at least. It was a decision, a conviction in something very significant, that in order to be born for the new, you have to die for the past. All ideals must be revaluated.

[Arvo Pärt 70. A radio series by Immo Mihkelson, Klassikaraadio, 2005, part 6]

This process of revaluation had already begun for some time earlier involving spiritual searchings, finding his belief and joining the Orthodox Church. These eight years of creative crisis were full of new ideas and experiments, but also disappointment and growing frustration. Arvo Pärt:

“I didn’t know at the time was I going to be able to compose at all in the future. Those years of study were no conscious break, but life and death agonising inner conflict. I had lost my inner compass and I didn’t know anymore, what an interval or a key meant.”

[Interview by Georg Koch and Michael Mönninger, Berliner Zeitung, March 1-2, 1997]

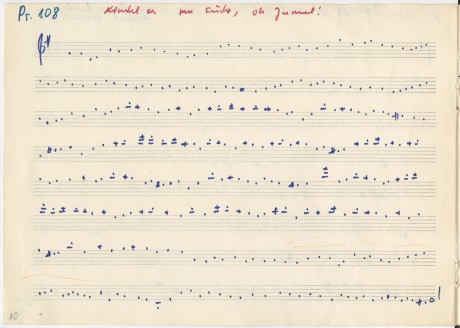

These sufferings are documented in Pärt’s musical notebooks or so-called musical diaries that Pärt started to use in 1974 to write down both his musical and verbal ideas. From these pages we see that the composer has drawn inspiration from many things, like Gregorian chant and early polyphony, scripture and prayers.

Pärt found his long searched own musical language in February, 1976 with a little piano piece Für Alina and in next two years he composed plenty of new works, like Cantus, Tabula rasa, Fratres, Spiegel im Spiegel, etc. He had created his original compositional technique which he called tintinnabuli and which has been the basis of his musical style up until today.

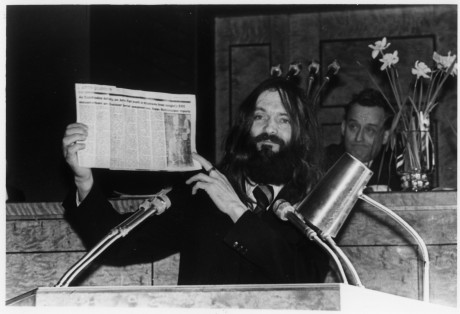

A dissident with a wig

It was February 16, 1979 during the XI Congress of Estonian SSR Composers’ Union, when Arvo Pärt stood up and held his notorius speech. His words created a scandal and started a process that eventually made Pärt and his family leave his homeland. In the overregulated atmosphere of do’s and don’ts, Pärt had had tense relationship with Soviet officials already with his earlier works, like Nekrolog or Credo, but this particular speech had a prelude.

When renowned Russian conductor Kirill Kondrashin fled the Soviet Union in December, 1978, and asked political asylum in Netherlands, the bans and borders were immediately tightened for everyone else who stayed. It was the same day when Arvo Pärt’s Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten was supposed to be performed in London by BBC Symphony Orchestra and Gennady Rozhdestvensky, but on the last minute Pärt’s license to travel was taken back and he couldn’t make it on the plane. A few days later, The Guardian published an anti-Soviet article by Finnish music critic Seppo Heikinheimo who told the whole story to the Western world and called Pärt a dissident.

All of these events pushed Pärt to hold a short but shocking speech at the Composers’ Union Congress, ridiculing the Soviet officials for creating such a scandal with their own strict rules, at the same time wearing a long haired wig as if pretending to be a different person, the alleged dissident.

After that, Pärts started to get several “recommendations“ to leave the country. And so they did in January, 1980.

We are going on a trip around the world and one day we will come back,

[Arvo Pärt 70. A radio series by Immo Mihkelson, Klassikaraadio, 2005, part 8]

the parents said to their little children when they asked where we are going. This dream eventually came true in 2010 when Arvo and Nora Pärt moved back to Estonia.

A road trip that changed everything

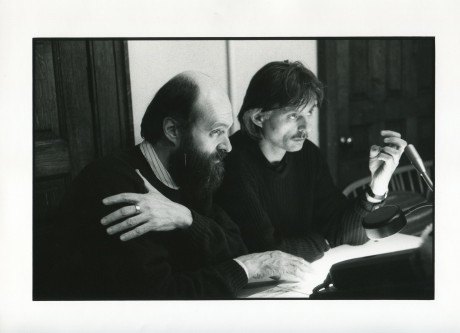

It might have been in 1980 when Manfred Eicher – the founder and producer of the record company ECM – drove his car from Stuttgart to Zürich and suddenly heard something so amazing from the radio, that he just had to stop the car and listen on. Only later did he find out that the music broadcasted by Radio Yerevan was the piece called Tabula rasa, a double concerto from 1977 by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. According to Eicher, he had never heard something like this before, and immediately he had an idea that this is the kind of music he wanted to record and release.

And so it happened. In 1984, ECM released the CD Tabula rasa, the first fruit of Manfred Eicher’s cooperation with Arvo Pärt, which changed everything. It was this CD that brought Pärt’s music to such a wide audience all over the world for the first time. And it was this CD that launched a whole new label of ECM recordings – ECM New Series – under which the most important all-Pärt albums and many of his first recordings have been released.

Since then, Pärt’s music has gained the love of a vast and surprisingly diverse audience, the music critics among them, outweighing by far the usual expectations to the popularity of classical music. His legacy has not only changed the course of contemporary classical music, but also left its footprints into the pop culture in a broader sense. His works have found their way into many films, choreographies, art and theatre projects, and they echo from the music of many pop artists as well.